Taking some liberties with Shannon’s and Weaver’s model of communication, I present two models of scholarly communication: our current one, and our final one.

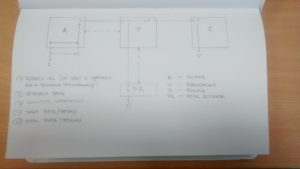

State of the art

The current system of scholarly communication is represented by the model below.

Description: Author (A) starts with a research idea (1). Upon defining a hypothesis and a research methodology, (A) collects an appropriate sample of research data (2). Analyzing (2) relative to (1) outputs a scientific information (3). The whole bundle (1), (2) and (3) is then encoded into a message to be transmitted — a draft paper (4).

(A) transmits the encoded message to a publication (P). It seeks out a peer reviewer (PR) to decode (4) and verify its integrity. Due to the noisy nature of encoding (1), (2), and (3) into a single literary form, decoding failures may possibly distort the scientific information (3?).

Decoding failures may at this point be queried by (PR), and relayed via (P) back to (A) for further clarification. The back-and-forth is represented by the dotted-line process; the author’s re-encoding of (4) relative to feedback received from (PR) yields a final paper (4′).

Upon receiving the final paper, a reader (R) — just like (PR) a step before — faces equal prospect of decoding failures distorting (3?), but without the privilege to query (A) for further clarification.

Moving forward

Two critical bottlenecks identified by the above model are: the author’s encoding process (subject to a plethora of cognitive biases, conflicts of interest, etc.), and the dotted-line feedback process (which may take a long time, and is of questionable utility due to author’s feedback itself being another product of author’s encoding). One other important implication of the above model is that both (PR) and (R) essentially engage in the same activity — decoding (4) and trying to derive (3) from it.

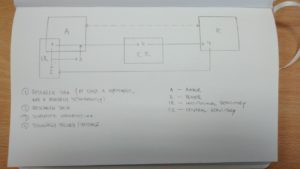

With those three pain points taken into consideration, the optimal system of scholarly communication — in terms of both efficiency and economy — is represented by the following repository-based model.

Description: Author (A) starts with a research idea (1). A hypothesis must be reduced to a single statement that shall be either true or false relative to research data (2). Upon defining such a hypothesis, (A) may proceed create a scholarly record (4) in a central repository (CR). Upon defining a research methodology, (A) collects an appropriate sample of (2). Analyzing (2) relative to (1) outputs scientific information (3), which is then encoded into (4) in a single bit (true/false).

(1) and (2) are captured in (A)’s institutional repository (IR), and persistently linked to (4). Each complete (4) ultimately contains: a central hypothesis defined in (1), persistent links to (1) and (2), and output (3) relative to them.

A reader (R) reviewing (4) is easily able take a closer look at (1) and (2) in the (IR), and ultimately dispute the validity of (3) and integrity of (4) if warranted by presence of methodological or interpretational issues. Feedback — represented by the dotted-line process — may be exchanged between (A) and (R) at any point after a (4) is created.

This model ensures that the ultimate size of each message — a scientific record — transmitted via (CR) is kept minimal: size of hypothesis + size of links to (1) and (2) + that 1 bit of (3).