A simple method to derive an article-level impact indicator from Journal Impact Factors (JIFs) is described here. I can’t vouch for its novelty, but I didn’t find anything quite similar reviewing the literature. Thanks mostly to Waltman and Traag I did learn about two proposals to fuse JIFs and citation counts/networks into hybrid impact indicators — namely by Abramo et al., and Levitt and Thelwall — however those take a different approach.

The logic behind this indicator is quite simple too. We (mis)use JIFs to evaluate individual articles. We (mis)use citation counts to evaluate individual articles. Would we end up with something at least as useful if we take JIFs of citing articles into account? I hope so.

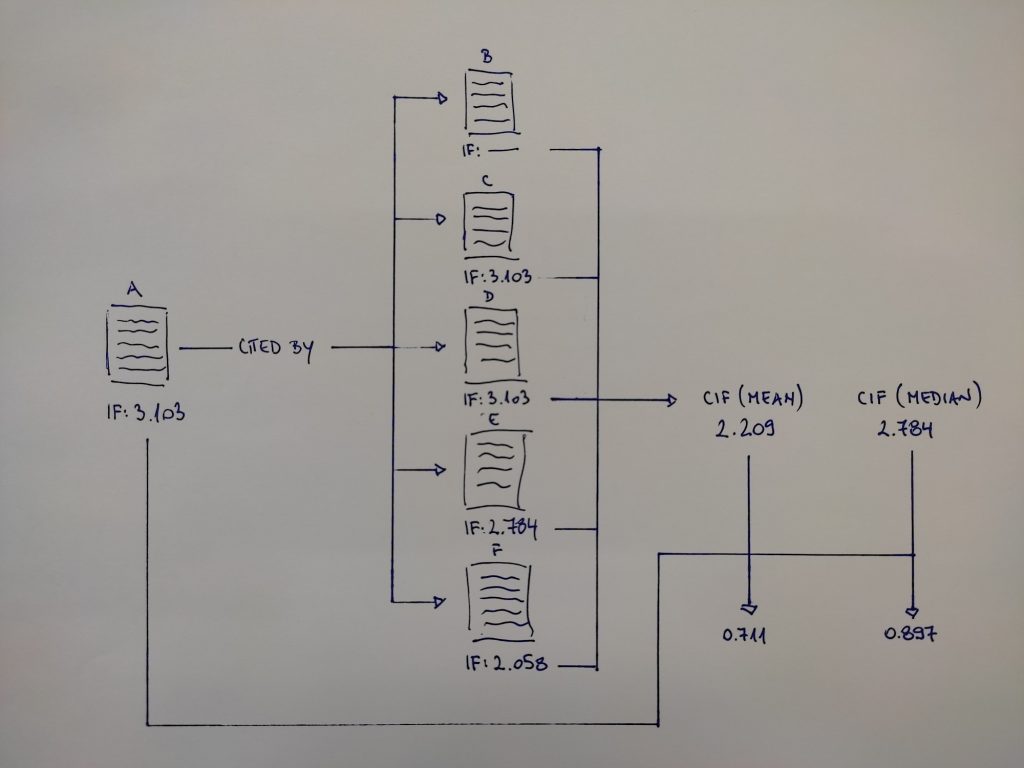

The way it works is perhaps best visually represented in Figure 1. Basically, we look up citations to paper A — there’s five of them here labeled B-F — and list the citing papers’ JIFs. Based on that list we calculate paper A’s… let’s call it Citing Impact Factor (CIF). We can go with mean or median values, whichever is more appropriate. This is the most complicated and tedious part.

Once we know our paper’s CIF we compare it to its JIF and interpret the results. In this particular case we see that the mean CIF (2.209) is ~0,9 lower than the JIF (3.103) — looks bad at first glance but that’s mostly owing to that 0 JIF paper B (should those be excluded? let me know). The median CIF (2.784) is more in line with the paper’s JIF, but we could say it’s slightly underperforming. We also see that our paper attracted 5 citations in the JIF calculation window, which is more than its JIF promised.

So what does this all tell us about our paper A? It’s not exceptional obviously, but it’s not bad either. It’s okay. In quantitative terms it overperforms — it scored 5 citations even though we expected 3 based on JIF. In qualitative terms its impact was limited — it hasn’t rippled through literature higher up in the hierarchy, but didn’t fizzle out completely either. We can characterize it as a small impact with localized effect.

To boil it down to an even more intuitive heuristic we can calculate CIF / JIF (Figure 1, bottom-right). That way we end up with a single figure similar to the Article Influence Score — if it’s greater than 1, that’s a positive indication; if it’s less than 1, that’s a negative indication. Obviously this doesn’t work as intended for 0 JIF papers — better stick with CIF for those.

That’s it. I picked the most boring example to demonstrate how the JIF can be conceived of as a promise of impact for a given paper, and its citation count + CIF as a manifestation of its impact. Given how elusive the measurement of impact is CIF might be useful, even if only as an additional data point to consider along the ubiquitous JIF — it’s certainly no panacea metric.

The least boring examples in my experience with CIF so far are the edge cases — works appearing in publications that don’t or can’t have a JIF. Those are the ones that regularly get less or no recognition in research evaluation exercises, and CIF might help us gauge where in the established JIF-based hierarchy of journals such papers would fit in. My favorite so far is a paper published in a 0 JIF journal, but with a mean CIF of 5.207 and a median CIF of a whopping 6.789 based on 24 citations! A veritable Q1 paper by that measure, but most likely to be glossed over in research evaluation.

To wrap it up: a tentative list of advantages and disadvantages of CIF.

Advantages:

- it’s based on JIF, a metric we’re all familiar with

- it’s simple to calculate and easy to use (and WOS could conceivably automate its calculation for WOS-indexed subset of works), with no extra weighing, normalization, etc. involved

- it can be used to evaluate non-indexed content and discover hidden gems in the literature

Disadvantages:

- it’s based on JIF, a metric we’re all familiar with

- it’s useless for evaluation of top-JIF papers since their impact is more likely to ripple downwards through the journal hierarchy

- it has no predictive ability since it takes time for a paper to accrue a meaningful number of citations for CIF calculation

References:

Abramo G, D’Angelo CA, Felici G. Predicting publication long-term impact through a combination of early citations and journal impact factor. Journal of Informetrics. 2019 Feb 1;13(1):32-49. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2018.11.003

Levitt JM, Thelwall M. A combined bibliometric indicator to predict article impact. Information Processing & Management. 2011 Mar 1;47(2):300-8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2010.09.005

Waltman L and Traag VA. Use of the journal impact factor for assessing individual articles: Statistically flawed or not? [version 2; peer review: 2 approved]. F1000Research. 2021, 9:366 doi: https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.23418.2